It’s fun to look back at decades past with rose-coloured glasses on. The big hair. The fluoro colours. The Sony Walkman and the great, great movies. And no, I’m not a millennial who’s pining over something that I never really knew; I’m old enough and jaded enough to have lived through the decade and to realise that it wasn’t all wine, roses and Tab Cola.

I remember Chernobyl and the ever present cold war. I have lived through the global epidemics and the numerous sectarian wars of the decade. And the terrorism. And the famines. What a depressing mess all that was. The more you look at the 80s, the more the superficial stuff dissolves and the more you realise just how far we’ve come in the 40 years that have passed since then.

A similar fate awaited Giles and Andy from Sydney’s Sabotage Motorcycles when they took a long, hard look at a customer’s 1981 Suzuki Katana GS650. And while their challenge may not have been on the scale of, say, stopping global thermonuclear war, there’s little doubt that they took on the motorcycle restoration equivalent of it. The painful look on their faces as they told me that there was pretty much nothing on the bike that wasn’t replaced, repaired or re-fabricated told a headache-inducing story of an ever-growing list of issues that all had to be remedied before the bike would be ready to ride. Ouch.

But first, a little context. “Well, we’ve spent since Christmas moving our whole shop to a new premises, ” says co-owner and co-wrencher, Giles Colliver. “It’s never a fun job, but the new workshop will make us way more efficient. We’ll be doing more motorcycle community events, such as swap meets, talks, rides, and more. We have some really exciting builds that we’re working on this year too. We can’t say too much about them at this point, but watch this space…”

And as casually as Giles said that, remember that they’ve both been moving and restoring the Suzuki Katana, too. Why do things the easy way, boys? Of course this is not a custom build, but rather a complete restoration that is taking a very sad, sorry-looking stock bike back to factory finish, or as close as possible to. And for those who are too young to remember the original bike’s specs, Giles helps out by jogging our memories. “The bike has a bikini fairing, 4-into-2 exhaust, a sporty lean-forward riding position, and of course an in-line four cylinder engine. I guess you could call it a kind of ‘80s factory cafe racer if you wanted to?” Works for me.

Off the back of the original 1100 bike’s success, Suzuki expanded the family to include a 550, 750, 1000 and this, the 1981 Suzuki GS650 Katana with the shaft drive. It’s the baby of the Katana family and believe it or not, the current owner of this bike is the same guy that originally purchased it back in the day. Now that’s commitment.

“This is a fairly rare story where the owner bought the bike from new,” smiles Giles. “He got it straight off the showroom floor back in ’81. It was ridden heaps in those early decades – all around Australia – as the owner was in the Australian Navy at the time.” Then a new family meant the bike got less and less tarmac time, and unfortunately it was also exposed to the Aussie sun for very long periods of time, meaning it fell into disrepair and was seriously weather beaten. Or as Giles notes, “One mate who saw it in the shop after it had been dropped off quipped, ‘Whoa, was that thing set on fire?’”

Giles and Andy knew they had our work cut out when we started peeling the bike’s layers back. Not a single washer, grommet, bracket or bolt could be cleaned and put back on the bike. Every part needed significant attention or replacement. They would really be earning their keep on this job, and then some. This was confirmed when the owner briefed them to get it back to the same factory finish as he saw that day on the showroom floor in 1981.

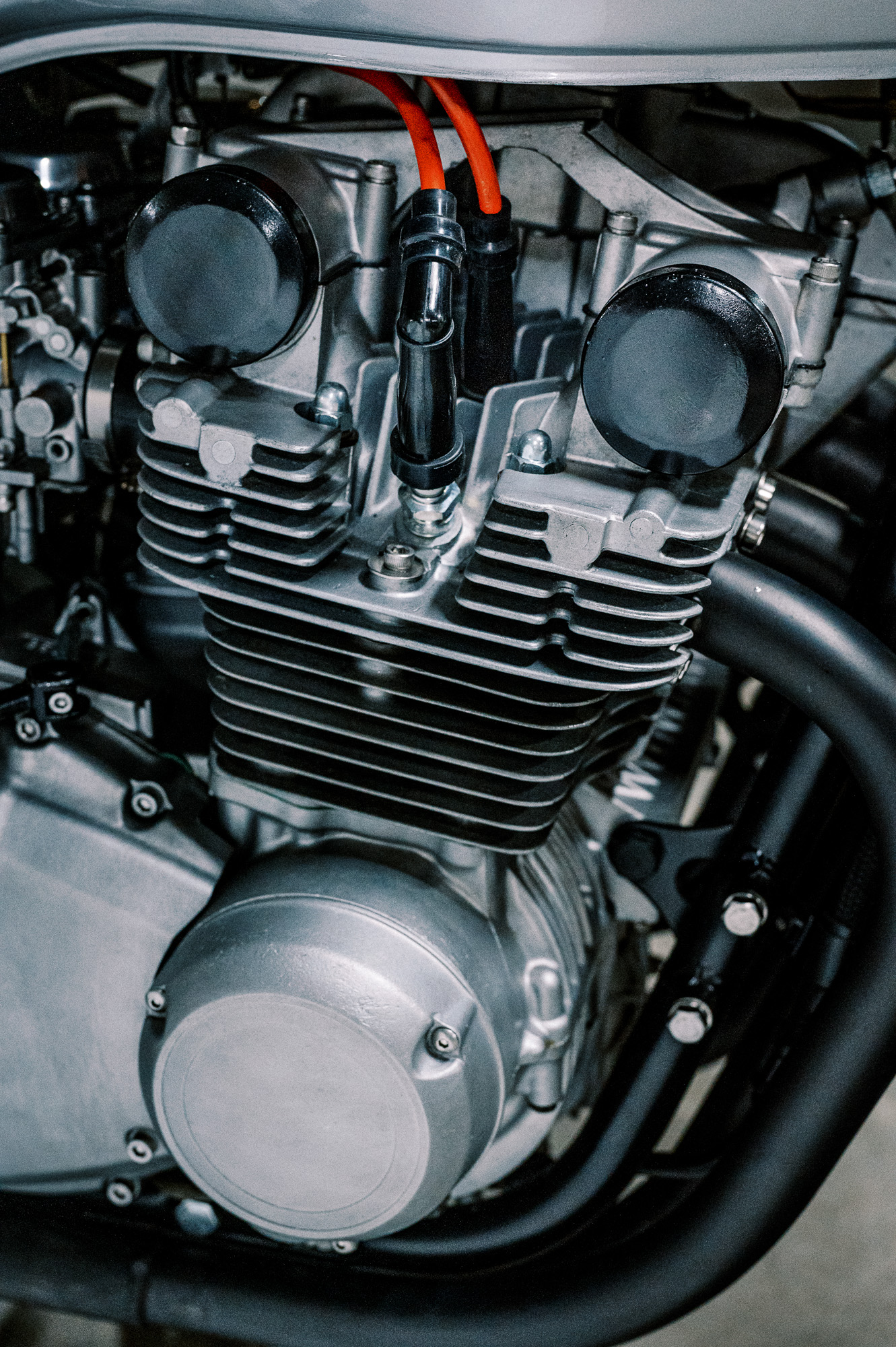

“Everything got stripped down,” continues Giles. “The painted parts were sent to our mate Kyle Smith, and the brake calipers and discs were Cerakoted. These were the only two parts of the build that we outsourced. The engine was fully rebuilt with the cylinders honed, and the valves re-lapped. Then the frame was blasted and powder coated followed by a full rewire, but using as manyof the old components that we could.”

Andy says that the forks were so badly corroded they needed to be machined down and re-chromed. They even reconditioned the old ignition coils as you can’t get this particular shade of orange high tension lead any more. “We were able to bring those back to retain the bright orange splashes throughout the bike,” he says.

Giles continues by explaining the amount of attention that the bike needed. “With every piece needing a lot of love and affection, we pulled in all of our skills to get this bike done and back on the road. For instance, the seat pan was so rusted through it more closely resembled a piece of Swiss cheese than a shaped bit of sheet metal. So we layered it with fiberglass to bring back some rigidity and to also provide a good base for the seat foam. The whole thing was then re-upholstered.”

And what do the gents like most about the completed project? “That we actually completed this project,” quips Giles. “It really was a huge undertaking on a bike where parts are not common, and it was probably too far gone for a resto. But we stuck to our guns and persevered. The owner’s face when we revealed it to him was also very cool; clearly it brought back so many memories and emotions for him. It was great to see”

The moral of this story is simple. Be it a customising request or complete restoration, no job involving a forty-year-old motorcycle is going to be an easy task. A builder might be happy that the bike only had one owner, because he will have a pretty good idea of the bike’s history, spills and thrills. Yes, time heals all wounds. But it also creates quite a few of its own, too – just ask Giles and Andy.

Sabotage Motorcycles – Facebook – Instagram

Images by Machines That Dream